[iad]

귀류법

07fl--722-LOGI/귀류법.txt

http://academy007.tistory.com/243

http://academy007.tistory.com/entry/귀류법

| ◈Tok kum 2015/03/28/토/15:35 |

그런데 이 사실을 직접 밝히는 것이 곤란하다면,

중론과 같은 논서에서는 이런 상대의 주장을 고집하면

『중론』sinsu 30. p.07a19 是不成難問 俱同於彼疑 4-9) 만일 누군가가 난문(상대의 주장을 비판하는 내용)이 있는데

sarvaṃ tasyānupālabdhaṃ samaṃ sādhyena jāyate// 원래 현실에서 사람들이 상식적으로 관념으로 분별한 다음 감각현실에서도 그대로 있고 그처럼 그 내용 그대로 실재한다는 주장을 깨뜨리기 위하여 여러가지 방식으로 논증을 펼치고 있는 것이다. 따라서 자신도 만일 그런 이의 주장을 만나면 우선 관념 영역안에서도 형식 논리적으로도 자체적으로 모순된 결론을 얻게 됨을 제시하여 그런 내용을 얻을 수 없음을 제시할 수 있다. 그로 인해 갖게 되는 모순점을 밝혀서

○ [pt op tr] mus0fl--France Gall - Si Maman Si.lrc

|

|

문서정보

ori

http://academy007.tistory.com/243#7930 07fl--722-LOGI/귀류법.txt ☞◆tdoz7930 |

>>>

귀류법

귀류법(歸謬法, 문화어: 귀유법)은

어떤 주장에 대해 그 함의하는 내용을 따라가다보면

이치에 닿지 않는 내용 또는 결론에 이르게 된다는 것을 보여서

그 주장이 잘못된 것임을 보이는 것이다.

'배리법'(背理法) 또는 '반증법'(反證法)이라고 일컬어지기도 한다.[1]

귀류법은 간접증명법이다.[2] [3] [4]

영어권에서는 라틴어로 "레둑티오 아드 아브수르둠(Reductio ad absurdum)"이라고 하며

이것의 해당 영어 번역은 "리덕션 투 더 업설드(reduction to the absurd)"이다.

수학에서는 특히 귀류법 또는 배리법이라고 부르며,

수학의 귀류법은 어떤 수학적 명제가 참인 것을 증명하는 수학적 증명 방법 중 하나이다.

수학의 귀류법은 영어로 "Proof by contradiction (프루프 바이 컨트러딕션 · 모순에 의한 증명)"이라고 한다.

단어들의 의미[편집]

문자 그대로의 뜻에 의거할 때,

귀류법 · 배리법 · 반증법 · 레둑티오 아드 아브수르둠 등의 단어들의 뜻은 다음과 같다.

- 귀류법(歸謬法): 오류로 귀착된다는 것을 보임

- 배리법(背理法): 이치에 어긋나게 된다는 것을 보임

- 반증법(反證法): 반대 증거가 나타나게 된다는 것을 보임

- 레둑티오 아드 아브수르둠(Reductio ad absurdum): 터무니 없는 것으로 돌아가게 되는 것을 보임

수학의 귀류법[편집]

수학에서 귀류법 · 배리법은

증명하려는 명제의 결론이 부정이라는 것을 가정하였을 때

모순되는 가정이 나온다는 것을 보여,

원래의 명제가 참인 것을 증명하는 방법이다.

귀류법은 유클리드가 2000년 전

소수의 무한함을 증명하기 위해 사용하였을 정도로

오래된 증명법이다.

예를 들어  가 유리수가 아님을

가 유리수가 아님을

귀류법으로 증명하기 위해서는

다음과 같은 과정을 따른다.

가 유리수라고 가정한다.

가 유리수라고 가정한다.

따라서 으로 둘 수 있다.

으로 둘 수 있다.

( 는 서로소인 자연수)

는 서로소인 자연수) 이므로

이므로  는 2의 배수이다.

는 2의 배수이다.  이 2의 배수이므로,

이 2의 배수이므로,  도 2의 배수이다.

도 2의 배수이다.

따라서 로 둘 수 있다.

로 둘 수 있다.

(여기서 는 자연수)

는 자연수) 이므로

이므로  은 2의 배수이다.

은 2의 배수이다.  이 2의 배수이므로,

이 2의 배수이므로,  도 2의 배수이다.

도 2의 배수이다.- 이는

가 서로소라는 가정에 모순이다.

가 서로소라는 가정에 모순이다.

따라서 는 유리수가 아니다.

는 유리수가 아니다.

함께 보기[편집]

- 논증(Argument)

- 추론(Inference · Reasoning)

- 연역법(Deductive reasoning)

- 귀납법(Inductive reasoning)

- 증명(Mathematical proof)

- 수학적 귀납법(Mathematical induction)

각주[편집]

- Nicholas Rescher. “Reductio ad absurdum” (영어). 《The Internet Journal of Philosophy》. 2011년 1월 25일에 확인함.

- 차길영. 귀류법에 관하여. 경인일보. 2010년 1월 24일.

- 김경. 2015 수시 논술중심전형 수리논술 대비 방안. 베리타스알파. 2014년 9월 15일.

- 조홍재. ‘수열’ 파트 증명 문제 어떻게. 세계일보. 2014년 7월 27일.

| 이 글은 수학에 관한 토막글입니다. 서로의 지식을 모아 알차게 문서를 완성해 갑시다. |

>>>

Proof by contradiction

In logic, proof by contradiction is a form of proof, and more specifically a form of indirect proof, that establishes the truth or validity of aproposition by showing that the proposition's being false would imply a contradiction. Proof by contradiction is also known as indirect proof,apagogical argument, proof by assuming the opposite, and reductio ad impossibilem. It is a particular kind of the more general form of argument known as reductio ad absurdum.

G. H. Hardy described proof by contradiction as "one of a mathematician's finest weapons", saying "It is a far finer gambit than any chessgambit: a chess player may offer the sacrifice of a pawn or even a piece, but a mathematician offers the game."[1]

Contents

[hide]Examples[edit]

Irrationality of the square root of 2[edit]

A classic proof by contradiction from mathematics is the proof that the square root of 2 is irrational.[2] If it were rational, it could be expressed as a fraction a/b in lowest terms, where a and b are integers, at least one of which is odd. But if a/b = √2, then a2 = 2b2. Therefore a2 must be even. Because the square of an odd number is odd, that in turn implies that a is even. This means that b must be odd because a/b is in lowest terms.

On the other hand, if a is even, then a2 is a multiple of 4. If a2 is a multiple of 4 and a2 = 2b2, then 2b2 is a multiple of 4, and therefore b2 is even, and so is b.

So b is odd and even, a contradiction. Therefore the initial assumption—that √2 can be expressed as a fraction—must be false.

The length of the hypotenuse[edit]

The method of proof by contradiction has also been used to show that for any non-degenerate right triangle, the length of the hypotenuse is less than the sum of the lengths of the two remaining sides.[3] The proof relies on the Pythagorean theorem. Letting c be the length of the hypotenuse and a and b the lengths of the legs, the claim is that a + b > c.

The claim is negated to assume that a + b ≤ c. Squaring both sides results in (a + b)2 ≤ c2 or, equivalently, a2 + 2ab + b2 ≤ c2. A triangle is non-degenerate if each edge has positive length, so it may be assumed that a and b are greater than 0. Therefore, a2 + b2 < a2 + 2ab + b2 ≤ c2. The transitive relation may be reduced to a2 + b2 < c2. It is known from the Pythagorean theorem that a2 + b2 = c2. This results in a contradiction since strict inequality and equality are mutually exclusive. The latter was a result of the Pythagorean theorem and the former the assumption thata + b ≤ c. The contradiction means that it is impossible for both to be true and it is known that the Pythagorean theorem holds. It follows that the assumption that a + b ≤ c must be false and hence a + b > c, proving the claim.

No least positive rational number[edit]

Consider the proposition, P: "there is no smallest rational number greater than 0". In a proof by contradiction, we start by assuming the opposite, ¬P: that there is a smallest rational number, say, r.

Now r/2 is a rational number greater than 0 and smaller than r. (In the above symbolic argument, "r/2 is the smallest rational number" would be Qand "r (which is different from r/2) is the smallest rational number" would be ¬Q.) But that contradicts our initial assumption, ¬P, that r was thesmallest rational number. So we can conclude that the original proposition, P, must be true — "there is no smallest rational number greater than 0".

Infinity of primes[edit]

Assume that the number of prime numbers is finite. There is thus an integer, p which is the largest prime.

p! (p-factorial) is divisible by every integer from 2 to p - 1, as it is the product of all of them and p. Hence, p! + 1 is not divisible by every integer from 2 to p - 1 (it gives a remainder of 1 when divided by each). p! + 1 is therefore either prime or is divisible by a prime larger than p.

This contradicts the assumption that p is the largest prime. The conclusion is that the number of primes is infinite.[4]

Other[edit]

For other examples, see proof that the square root of 2 is not rational (where indirect proofs different from the above one can be found) andCantor's diagonal argument.

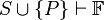

In mathematical logic[edit]

In mathematical logic, the proof by contradiction is represented as:

- If

- then

or

- If

- then

In the above, P is the proposition we wish to prove, and S is a set of statements, which are the premises—these could be, for example, theaxioms of the theory we are working in, or earlier theorems we can build upon. We consider P, or the negation of P, in addition to S; if this leads to a logical contradiction F, then we can conclude that the statements in S lead to the negation of P, or P itself, respectively.

Note that the set-theoretic union, in some contexts closely related to logical disjunction (or), is used here for sets of statements in such a way that it is more related to logical conjunction (and).

A particular kind of indirect proof assumes that some object doesn't exist, and then proves that this would lead to a contradiction; thus, such an object must exist. Although it is quite freely used in mathematical proofs, not every school of mathematical thought accepts this kind of argument as universally valid. See further Nonconstructive proof.

Notation[edit]

Proofs by contradiction sometimes end with the word "Contradiction!". Isaac Barrow and Baermann used the notation Q.E.A., for "quod est absurdum" ("which is absurd"), along the lines of Q.E.D., but this notation is rarely used today.[5] A graphical symbol sometimes used for contradictions is a downwards zigzag arrow "lightning" symbol (U+21AF: ↯), for example in Davey and Priestley.[6] Others sometimes used include a pair of opposing arrows (as  or

or  ), struck-out arrows (

), struck-out arrows ( ), a stylized form of hash (such as U+2A33: ⨳), or the "reference mark" (U+203B: ※).[7][8] The "up tack" symbol (U+22A5: ⊥) used by philosophers and logicians (see contradiction) also appears, but is often avoided due to its usage for orthogonality.

), a stylized form of hash (such as U+2A33: ⨳), or the "reference mark" (U+203B: ※).[7][8] The "up tack" symbol (U+22A5: ⊥) used by philosophers and logicians (see contradiction) also appears, but is often avoided due to its usage for orthogonality.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- G. H. Hardy, A Mathematician's Apology; Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 9780521427067. p. 94.

- Alfield, Peter (16 August 1996). "Why is the square root of 2 irrational?". Understanding Mathematics, a study guide. Department of Mathematics, University of Utah. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- Stone, Peter. "Logic, Sets, and Functions: Honors". Course materials. pp 14–23: Department of Computer Sciences, The University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- Further Pure Mathematics, L Bostock, F S Chandler and C P Rourke

- Hartshorne on QED and related

- B. Davey and H.A. Priestley, Introduction to lattices and order, Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- The Comprehensive LaTeX Symbol List, pg. 20. http://www.ctan.org/tex-archive/info/symbols/comprehensive/symbols-a4.pdf

- Gary Hardegree, Introduction to Modal Logic, Chapter 2, pg. II–2. http://people.umass.edu/gmhwww/511/pdf/c02.pdf

Further reading[edit]

| The Wikibook Mathematical Proof has a page on the topic of: Proof by Contradiction |

- Franklin, James (2011). Proof in Mathematics: An Introduction. chapter 6: Kew. ISBN 978-0-646-54509-7.[dead link]

External links[edit]

- Proof by Contradiction from Larry W. Cusick's How To Write Proofs

This page was last modified on 9 March 2015, at 18:59.

>>

>>>

Reductio ad absurdum

Reductio ad absurdum (Latin: "reduction to absurdity"; pl.: reductiones ad absurdum), also known as argumentum ad absurdum (Latin: argument to absurdity), is a common form of argument which seeks to demonstrate that a statement is true by showing that a false, untenable, orabsurd result follows from its denial,[1] or in turn to demonstrate that a statement is false by showing that a false, untenable, or absurd result follows from its acceptance. First recognized and studied in classical Greek philosophy (the Latin term derives from the Greek "εις άτοπον απαγωγή" or eis atopon apagoge, "reduction to the impossible", for example in Aristotle's Prior Analytics),[1] this technique has been used throughout history in both formal mathematical and philosophical reasoning, as well as informal debate.

The "absurd" conclusion of a reductio ad absurdum argument can take a range of forms:

- Rocks have weight, otherwise we would see them floating in the air.

- Society must have laws, otherwise there would be chaos.

- There is no smallest positive rational number, because if there were, then it could be divided by two to get a smaller one.

The first example above argues that the denial of the assertion would have a ridiculous result; it would go against the evidence of our senses. The second argues denial of the assertion would be untenable; unpleasant or unworkable for society. The third is a mathematical proof by contradiction, arguing that the denial of the premise would result in a logical contradiction (there is a "smallest" number and yet there is a number smaller than it).

Contents

[hide]Greek philosophy[edit]

This technique is used throughout Greek philosophy, beginning with Presocratic philosophers. The earliest Greek example of a reductio argument is supposedly in fragments of a satirical poem attributed to Xenophanes of Colophon (c.570 – c.475 BC).[2] Criticizing Homer's attribution of human faults to the Greek gods, he says that humans also believe that the gods' bodies have human form. But if horses and oxen could draw, they would draw the gods with horse and oxen bodies. The gods can't have both forms, so this is a contradiction. Therefore the attribution of other human characteristics to the gods, such as human faults, is also false.

The earlier dialogs of Plato (424 – 348 BC), relating the debates of his teacher Socrates, raised the use of reductio arguments to a formal dialectical method (Elenchus), now called the Socratic method.[3][4] Typically Socrates' opponent would make an innocuous assertion, then Socrates by a step-by-step train of reasoning, bringing in other background assumptions, would make the person admit that the assertion resulted in an absurd or contradictory conclusion, forcing him to abandon his assertion. The technique was also a focus of the work of Aristotle(384 – 322 BC).[4]

The principle of non-contradiction[edit]

Aristotle clarified the connection between contradiction and falsity in his principle of non-contradiction.[4] This states that an assertion cannot be both true and false. Therefore if the contradiction of an assertion (not-P) can be derived logically from the assertion (P) it can be concluded that a false assumption has been used. This technique, called proof by contradiction has formed the basis of reductio ad absurdum arguments in formal fields like logic and mathematics.[4]

The principle of non-contradiction has seemed absolutely undeniable to most philosophers.[4] However a few philosophers such as Heraclitusand Hegel have accepted contradictions.

The principle of explosion and Paraconsistent Logic[edit]

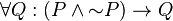

A curious logical consequence of the principle of non-contradiction is that a contradiction implies any statement; if a contradiction is accepted, any proposition (or its negation) can be proved from it. This is known as the principle of explosion (Latin: ex falso quodlibet, "from a falsehood, anything [follows]", or ex contradictione sequitur quodlibet, "from a contradiction, anything follows"), or the principle of Pseudo-Scotus.

"for all Q, P and not-P implies Q"

The discovery of contradictions at the foundations of mathematics at the beginning of the 20th century, such as Russell's paradox, threatened the entire structure of mathematics due to the principle of explosion. This has led a few philosophers such as Newton da Costa, Walter Carnielliand Graham Priest to reject the principle of non-contradiction, giving rise to theories such as paraconsistent logic and its particular form,dialethism, which accepts that there exist statements that are both true and false.

Paraconsistent logics usually deny that the principle of explosion holds for all sentences in logic, which amounts to denying that a contradiction entails everything (what is called “deductive explosion”). The Logics of Formal Inconsistency (LFIs) are a family of paraconsistent logics where the notions of contradiction and consistency are not coincident; although the validity of the principle of explosion is not accepted for all sentences, it is accepted for consistent sentences. Most paraconsistent logics, as the LFIs, also reject the principle of non-contradiction.[4]

Straw man argument[edit]

A fallacious argument similar to reductio ad absurdum often seen in polemical debate is the straw man logical fallacy.[5] A straw man argument attempts to refute a given proposition by showing that a slightly different or inaccurate form of the proposition (the "straw man") has an absurd, unpleasant, or ridiculous consequence, relying on the audience not to notice that the argument does not actually apply to the original proposition. For example, in a 1977 appeal of a U.S. bank robbery conviction, a prosecuting attorney said in his closing argument[6]

The prosecutor was using this "straw man" to attempt to alarm the appellate judges; the chance that any precedent set by this one particular case would literally make it impossible to convict any bank robbers was undoubtedly remote.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ b Nicholas Rescher. "Reductio ad absurdum". The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- Daigle, Robert W. (1991). "The reductio ad absurdum argument prior to Aristotle". Master's Thesis. San Jose State Univ. RetrievedAugust 22, 2012.

- Bobzian, Suzanne (2006). "Ancient Logic". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ b c d e f "Reductio ad absurdum". New World Encyclopedia. 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- Lapakko, David (2009). Argumentation: Critical Thinking in Action. iUniverse. p. 119. ISBN 1440168385.

- Bosanac, Paul (2009). Litigation Logic: A Practical Guide to Effective Argument. American Bar Association. p. 393. ISBN 1616327103. In the original citation, the closing quotation marks are (apparently by mistake) at the sentence's very end.

>>>

귀류법 보충자료

07fl--722-LOGI/귀류법-보충자료.txt

http://academy007.tistory.com/242

>>>

● 추가자료

다음 백과

http://100.daum.net/search/search.do?query=귀류법

네이버지식백과

http://terms.naver.com/search.nhn?query=귀류법

한국 위키백과

https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/귀류법

영어 위키 백과

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/귀류법

네이버 한자

http://hanja.naver.com/search?query=귀류법

네이버 지식

http://kin.naver.com/search/list.nhn?cs=utf8&query=귀류법

네이버 영어사전

http://endic.naver.com/search.nhn?isOnlyViewEE=N&query=귀류법

구글

https://www.google.co.kr/?gws_rd=ssl#newwindow=1&q=귀류법

네이버

http://search.naver.com/search.naver?where=nexearch&query=귀류법

다음

http://search.daum.net/search?w=tot&q=귀류법

다음 백과

귀류법

네이버지식백과

귀류법

한국 위키백과

귀류법

영어 위키 백과

귀류법

네이버 한자

귀류법

네이버 지식

귀류법

네이버 영어사전

귀류법

구글

귀류법

네이버

귀류법

다음

귀류법

다음 백과

http://100.daum.net/search/search.do?query=귀류법

네이버지식백과

http://terms.naver.com/search.nhn?query=귀류법

한국 위키백과

https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/귀류법

영어 위키 백과

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/귀류법

네이버 한자

http://hanja.naver.com/search?query=귀류법

네이버 지식

http://kin.naver.com/search/list.nhn?cs=utf8&query=귀류법

네이버 영어사전

http://endic.naver.com/search.nhn?isOnlyViewEE=N&query=귀류법

구글

https://www.google.co.kr/?gws_rd=ssl#newwindow=1&q=귀류법

네이버

http://search.naver.com/search.naver?where=nexearch&query=귀류법

다음

http://search.daum.net/search?w=tot&q=귀류법

>>>

>>>

>>>

>>>

![]()

Ш[ 관련 문서 인용 부분 ]Ш

ㅹ[ 코멘트 등 정리 내역]ㅹ

Ω♠문서정보♠Ω

™[작성자]™ Tok kum

◑[작성일]◐ 2015/03/28/토/15:34

♨[수정내역]♨

▩[ 디스크 ]▩ [DISK] 07fl--722-LOGI/귀류법.txt ♠

ж[ 웹 ]ж [web] http://academy007.tistory.com/243 ♠

⇔[ 관련문서]⇔

{!-- 관련 문서 링크--}

인터넷상의 목록 http://academy007.tistory.com/224

디스크상의 목록 ●논리학 07fl--722-LOGI/LOGI-catalog.htm

'722-logi-논리학-[내부연구용]' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 감각내용과 개념과의 관계 (0) | 2011.07.16 |

|---|---|

| 감각내용과 상응하는 관념의 성격 (0) | 2011.07.16 |

| 쌍칼 공격에 대응한 쌍창 공격법 (0) | 2011.07.11 |

| 아침의 논리공부 (0) | 2011.07.10 |

| ####금지와 개념-2 (1) | 2011.06.23 |